Planets and Dissertations

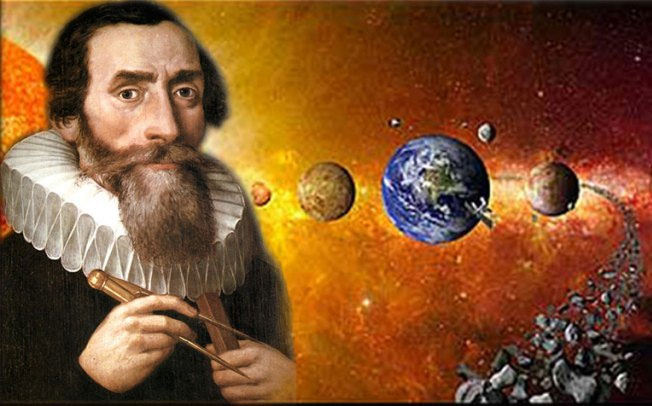

On July 19, 1595, Johannes Kepler had a great epiphany about the motion of planets in our solar system. In turns out that he got it terribly wrong at first, but that didn’t matter — a fact that should cause dissertation students to rejoice…

I’ve told you before that I’m a bit of a science geek — OK, more than a bit. I truly think that science, the pursuit of science, and the history of science can be very instructive in all aspects life.

So, what can we learn from something that happened over 400 years ago? First, let’s talk a little about what happened.

While lecturing about the fact that Saturn and Jupiter sometimes occupy the same part of the sky at the same time, Kepler realized that regular polygons set inside and around circles could account for the movements of the planets…

Before your head explodes, don’t worry about that. He was wrong. His idea had a lot to do with philosophies regarding divine perfection that guided much of scientific thought for centuries.

But — and here’s the point — he figured out that he was wrong and kept going. He tried using two-dimensional figures, then three-dimensional figures. Then, he started trying other things.

Eventually, he developed Kepler’s Three Laws of Planetary Motion — the same three we all learn in high school science class to this day.

“So, what does this have to do with me and my dissertation?” Everything.

The first draft you send in to your chair will be “wrong.” I don’t care if it’s your concept paper, your prospectus, your proposal, or your dissertation; it will be “wrong!”

I use the word, “wrong” in quotes because I don’t really mean wrong, as in right or wrong, true or false. Instead, I mean “wrong,” as in not exactly what you’re committee is looking for — wrong for them.

And, just like Kepler had data to tell him how his ideas were wrong, you have feedback from your committee to tell you how your ideas are “wrong.”

Scientists aren’t always right, but the scientific process helps them to move in the right direction. Dissertation students are never right — not at the start, anyway — but, the process of creating iterative drafts based on their committee members’ feedback helps them to move in the right direction.

So, don’t despair when you receive rivers of red ink from a committee member. Yes, it means that you have work to do, but it’s also the blueprint that shows you exactly how to do it.

Let’s say that you submit a draft and get back 100 comments. OK, that’s a lot. And, maybe you’re not happy with the review or the feedback.

But, remember that your goal is to graduate. And, the quickest path to graduation is through your committee’s approval. Indeed, that’s the onlypath to graduation! So, you address each issue and submit your work back to your committee.

Now, your reviewer really only has three options when reviewing your work this time around. For each of their previous comments they can determine that you fixed the issue, you did not fix the issue, or you fixed the issue but your fix broke something else. (That last one has to do with a concept called alignment, which we’ll leave for another day.)

That’s it! They can’t go and find dozens …or hundreds!… of more things for you to fix. Their previous review already identified all of the issues they had with your paper.

So, you worked on 100 issues, and the reviewer will likely consider the vast majority of them to be fixed. Now your draft comes back with just 30 of the original 100 issues requiring more attention.

You work on those. And, since there are less issues to deal with, the work goes faster. You submit your draft. It is reviewed and returned. And, this time, there are only seven issues outstanding.

A few quick edits and back to the committee. And, this time it’s approved!

This is how the iterative feedback process works. After just a few drafts you move from having over one hundred mistakes to an approved paper.

Through it all, remember that your goal is to graduate. Remember that you graduate when your committee members are happy with your dissertation. Work with them, not against them. Don’t argue minor points, just keep your head down and make the adjustments they request.

You started the doctoral program to finish. To graduate. To earn a doctoral credential so that you could make a bigger impact in the world!

Before long, you be moving on to the next stage of the process, and then the next stage, and, sooner than you imagine, you be on the commencement stage!

“I hear you, Dr. Strickland, and I want to keep things moving forward, but I don’t even understand my committee’s feedback most of the time!”